In this blog post, Sara Heikonen writes about her insights on remote learning that she has gained through two different roles: writing her master’s thesis in the Water and Development Research Group and working as a programme-level course assistant in the courses of Water and Environmental Engineering Master’s programme (WAT).

During the covid-19 pandemic, students, teachers, and researchers have faced the challenges of working from home and collaborating online. As for myself, I started working on my master’s thesis in the Water and Development Research Group in June 2020, and as a WAT course assistant with a special focus on supporting interaction in remote learning in January 2021. These experiences have shown me two different and interesting sides of remote work and remote learning: the perspective of a student and the perspective of a course staff member.

Based on my experience, two common challenges that both students and teaching staff have been facing are reduced connection to peers and co-workers (or between teachers and students), and reduced peer support. In online teaching, it might be challenging for the teacher to know whether the students are following and understanding the lecture topics as the students appear as just black boxes on the teachers’ screens. On the other hand, the students might feel intimidated to ask questions or keep their cameras on during online teaching sessions, and don’t have the opportunity to reflect and discuss with a fellow student during the sessions. In addition, there are no natural opportunities for casual interaction before and after lectures or on coffee breaks.

In the WAT Master’s programme, teachers and course assistants have made great efforts to strengthen the interaction between students and course staff, and to keep the lectures interesting and easy to follow during the remote teaching period. The interactive elements have been implemented with different online learning tools and in my experience, the world of online learning and collaboration tools can seem quite confusing and overwhelming. However, the individual tools play after all only a small role in the overall online learning experience and therefore it might be more important to focus on the practices of arranging online learning. Based on my experience from WAT courses, the three key factors that have made a difference towards more engaging online learning are:

- Providing opportunities for interaction, both between peers and between the students and the teachers.

- Careful scheduling of teaching or study sessions, including the breaks.

- Investing in supporting the students.

Below I give some examples of how these three key factors have been implemented in our courses and in the remote master’s thesis writing process.

1. Opportunities for interaction

In spring 2021 we have piloted weekly online writing and peer support sessions with our current master’s thesis workers. The sessions have aimed to provide structure and motivation for working from home, to promote sharing struggles and tips, and to offer an opportunity for casual interaction with peers as well. I would have loved to participate in these kinds of sessions when working on my own thesis if it had been possible! The sessions have been well received and have been found helpful. At the moment, the sessions attract two to five thesis writers weekly (around 50% of the students who are currently working on their theses. However, we would still like to reach more students and increase the number of regular participants.

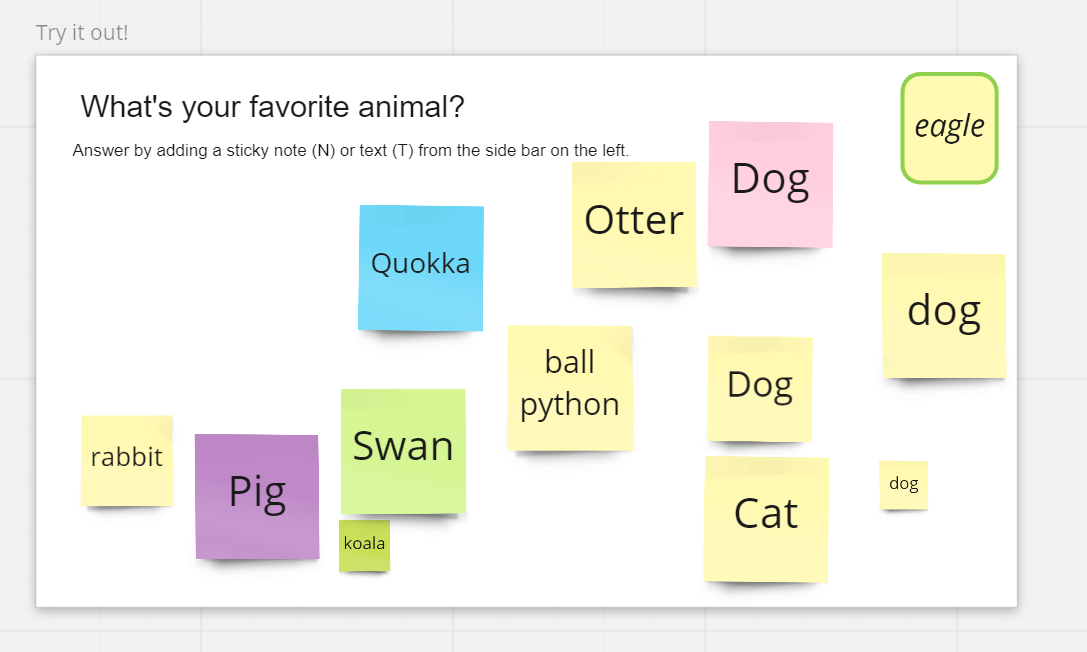

In the WAT courses, peer interaction and interaction between students and teachers have been supported in multiple ways. For example, in lectures students often get involved in activities that have a low threshold to participate: polls, small group discussions and exercises on online collaboration platforms such as Miro. In addition, in most courses, there have been group projects or opportunities to work together on assignments during exercise sessions.

Trying out an online collaboration platform with an ice breaker activity in the first lecture of a course.

2. Scheduling and breaks

Based on discussions with the master’s programme teachers, it seems that in online teaching, it’s more challenging to change the plans for a teaching session on the fly compared to classroom teaching. Therefore, careful planning of the session manuscripts has been even more important and useful than before. Moreover, special attention in the session scheduling needs to be put on reserving extra time for questions, discussion, the planned interactive elements of the lecture, and most importantly, for the breaks! Based on the feedback and experiences from our WAT courses, there should be a longer break at least once an hour, in addition to a few shorter breaks or interactive elements such as group discussions or polls. Frequent breaks help the students to stay focused and give also the teacher a chance to revise the schedule and the plan for the rest of the session.

3. Supporting the students

In online teaching, the students are working more independently than in classroom teaching because a large part of the usual peer support, gained through interaction during teaching sessions (and outside of them), is missing. In addition, assisting students with assignments is often slower and clumsier online than in person. To ensure that the students get the support that they need and don’t feel left alone with their challenges, it is important to build trust and connection between the students and the teachers, and often also to provide extra support with assignments.

In our master’s programme, trust and connection has been built for example by taking time for an introductory round with an icebreaker activity at the beginning of a course, and by having one on one discussions with all students during exercise sessions. For extra support with assignments, our master’s students have appreciated it if the teachers have scheduled weekly, optional support sessions for questions related to course assignments. In addition, if there has been a discussion forum for assignment related questions on the course platform, the students have been able to help each other, and the teachers have saved some time because they have been able to help multiple students at the same time.

Even though making changes to course arrangements or brainstorming ways to bring interactive elements from classroom teaching into the online learning environment might be challenging, I think it makes an important difference from the perspective of the students. Even small changes towards increasing interaction in online learning have an impact and students truly appreciate them. In the WAT master’s programme, this has really been considered, and I hope it has made this remote learning period more enjoyable for the students and the teachers.