Google Earth Engine is a cloud-based platform for geospatial analysis. It was the main tool used in Roope Kouki’s recent master’s thesis on agricultural drought in Finland. In this post, he considers the pros, cons, and applications of this new tool.

“Huh, I wonder if this would make it easier.” That was the general thought in the back of my mind when, right after starting the master’s thesis process back in March, I heard about Earth Engine (thanks to Maija Taka for getting me started with it). I had just finished downloading a several-hundred-megabyte file containing Landsat satellite imagery. By any estimate, I would have needed at least hundreds of these for what I was planning to do. There had to be an easier way (one that would not land me on the Aalto network administrators’ blacklist), and Earth Engine seemed to be it. With petabytes of archived satellite imagery and other data, it seemed like the perfect fit.

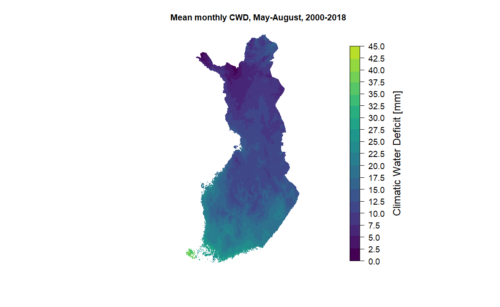

At the core of Earth Engine is the idea of harnessing big data and cloud-based computing for geospatial applications. Besides the extensive data catalogue, a user of the service gets access to Google’s considerable computing power. Application Programming Interfaces exist for Javascript and Python, in addition to which an online Integrated Development Environment (the Code Editor) is available. It was this online IDE that I used for my work. It is based on the Javascript API and includes an interactive map display, enabling the user to quickly prototype ideas and see how they play out. The service mostly handles scaling and projections in the background – the grids of all the datasets I used in my analysis did not match, but this was a non-problem, as Earth Engine has no trouble producing an uneven grid as an output.

One of the most obvious drawbacks of the platform is its lack of some of the features of a more ‘traditional’ GIS, such as the ability to manually manipulate tabular data and produce print-ready maps and figures. For the purposes of my work, I had to pair it with Excel for statistics and R for producing figures. Due to features of the platform’s architecture, it is also only suited to certain kinds of applications – namely running large numbers of relatively simple, parallelizable operations on massive amounts of data. While it is very handy for performing band-math on massively large images, it is not well suited to operations that are not easy to split into smaller pieces (the developers give watershed analysis as an example of an application Earth Engine is ill-suited for).

In summary:

- If you’re looking for a relatively pain-free way of handling massive amounts of remote sensing data, there is a good chance Earth Engine could help you (and a fair chance the data is already in the archive)

- Just don’t expect it to do everything you’re used to a GIS doing

- If you’re wondering whether it could be useful for a project, give it a quick try – the Code Editor is fairly user-friendly

- Would I use it again? Yes. For everything? No.

Roope Kouki wrote his master’s thesis, “The effects of drought on Finnish cereal grain production”, in the Water and Development Research Group.