Daniel Chrisendo

The efforts to protect women from dangerous and hazardous working conditions sometimes can go so far that they come across as inconsistent with gender equality. Protective legislation every so often tends to discriminate against women in getting employment and limit their movement. This is, of course, a puzzling situation, especially in a country where women remain extremely vulnerable to violence and constantly become victims. For justifiable reasons, achieving gender equality and empowering all women and girls is set to be one of the Sustainable Development goals.

“Daniel, I am offended by your results,” someone approached me after I finished my presentation. I was presenting my latest research at the 5th Global Land Program Open Science Meeting in Oaxaca, Mexico, in November 2024. In my 15-minute presentation, I showed how discrimination against women in agriculture correlates with lower crop yields globally.

“Why? Did I say something wrong?” I demanded clarification.

“You showed that Sudan is a country with the highest gender discrimination. You know I am from Sudan, and you did not give me a heads-up. I was shocked with the results,” she replied jokingly.

In my ongoing research, I developed an index indicating whether a country has laws that discriminate against women in six dimensions: discrimination in household responsibilities, access to land assets, access to non-land assets, access to financial services, inheritance, and freedom of movement, all related to women’s roles in agriculture. The results show that Sudan, Congo, Iran, and Swaziland have the highest discrimination, while Denmark, Sweden, Norway, and the USA are among the countries with the lowest discrimination. My results also show how the discrimination correlates with lower yields for over 75 crops worldwide.

The discussion among the 50 participants was crisp. I received many compliments, especially for the global discrimination maps that my colleague Sara Heikonen created. Some people approached me and said they wanted to use those maps in their research. But I also received criticism. The prominent one is the definition of discrimination in my study, which, according to a few, is a Western perspective.

I argued that where women’s movement is restricted by law, such as they cannot go outside with the permission or companionship of an adult male, their work in agriculture will be affected. They could not freely go to the farm to work or to the market to sell their crops, which would result in lower yields.

“I am glad that my government restricts my movement,” she continued speaking. “Going to the farm alone or out at night is so dangerous. I am glad that I always have to go with someone.”

Of course, I will never understand how it is to be a woman, let alone to live in a situation where I have to constantly worry about my personal safety. However, in an ideal, just, and safe world, women should be able to go anywhere and anytime without a guardian and still feel safe; nothing terrible should happen to them. Protecting women’s safety is really a good step. However, restricting their movement for protection violates their rights and does not solve the core problem.

The double-edged of women-only passenger cars

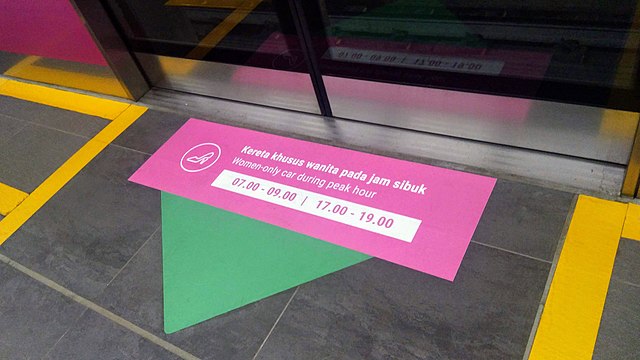

In Mexico City, Jakarta, and some other cities in Africa, Asia, and the Americas, sexual harassment and assault against women in public transportation have been a big issue. Addressing this problem, public transport introduces women-only passenger cars or areas in commuter trains and busses intended for women only, usually marked by its distinct pink color and flower symbol. Studies show that women welcome this initiative (e.g., Dunckel-Graglia, 2013; Abenoza et al., 2020), though it is less effective than surveillance cameras or police patrols (e.g., Shibata, 2019). It could also promote sexual segregation in some societies, one of the few reasons why this practice has been discontinued in the USA, Germany, and the UK.

Sign to enter women-only passenger car in Jakarta Mass Rapid Transit (source: Wikimedia Commons)

It could backfire, too. I remember a story from Jakarta that went viral: a woman was harassed in an all-gender passenger car. The perpetrator, a man, yelled that if she did not want to be harassed, she should board the women-only cars. This initiative may create an understanding that a safe space for women is cornered to women-only cars, and everywhere else is less safe. But this should not be the case. Women should feel safe in whichever car they board.

The hypermasculinity of the mining industry

In another opportunity, five Aalto University students and I visited Copperbelt province, Zambia, as part of Aalto’s Sustainable Global Technologies (SGT) course. Together with the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO), we were investigating women’s involvement in the mining industry. Zambia is a mining-intensive country with the sector’s contribution to the GDP of about 12% (Kolala and Dokowe, 2021). Copper, the country’s main extractive metal, is found in cellphones, coffee machines, and doorknobs, making it the seventh biggest copper producer in the world.

Like in other STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) disciplines, women are underrepresented in the Zambian mining industry. When I gave a guest lecture at the School of Mines and Mineral Sciences, Copperbelt University, many women students attended my talk. However, based on history, only a few will eventually make it to the industry.

“We are not allowed to work underground because we are women,” one student said.

Zambia has a law that, by default, prohibits women from working underground. Special permission from the government is required if they wish to work under the earth’s surface, which is not required for men. Even if permission is granted, they can only be underground for up to four hours a day and a few days a week.

According to the World Bank (2020), around 60 countries forbid women from working in underground mines, most of which are in Africa. Such a prohibition started far back in the 19th century when the British state attempted to regulate women’s labor in underground coal mines to protect them from poor and hazardous working conditions. The government enacted the Mines and Collieries Act of 1842, which later became the model for the International Labor Organization C45 Underground Work (Women) Convention of 1935. The Convention prohibited women from working under the earth’s surface. Around the same time, ILO enacted the C89 Night Work (Women) Convention, banning women from night work. Countries that signed the Convention must ratify it by translating it into national law, generally within one year. Those who do not comply with the Convention may face certain “punishment.”

Lahiri Dutt (2020) explains how vast the consequences are, intendedly and unintendedly, and not necessarily relevant to the situation in the 19th-century UK. For one, it pushed women out of stable formal employment instead of protecting them. Since women stopped working in mining almost one hundred years ago, it has also been hyper-masculinizing the mining industry, giving the impression that only men can perform complex tasks underground. It started to be difficult to imagine women working underground.

Over time, the law faced many challenges, including accusations of employment discrimination based on gender. In 2002, the ILO itself denounced the C45 Underground Work (Women) Convention (the C89 Convention had been denounced much earlier). Finland, for example, denounced the C45 Convention in 1997, five years earlier than ILO itself. This event was followed by many countries worldwide abolishing the law prohibiting women underground, though many still have the law in place. Meanwhile, Zambia is an interesting case. Though the country denounced the C45 Convention in 1998, a national law that prohibits women from working underground still exists at least until the time we were in Zambia in March 2024.

While in Copperbelt, I visited an underground copper mine just a bit deeper than 1.5 km (the highest point in Finland is around 1.3 km). My students (four of them were women) and I were given overalls, helmets, boots, and headlamps as protective measures before entering the mine. Each of us had to bring a rescue pack attached to our special belt that would generate oxygen for 25 minutes if there was no breathable air underground, especially due to fire and explosion, while waiting for external rescue.

We rode an elevator that could transport 50 people at once to the depth we wanted in just six minutes. As the altitude changed quickly, my ears started to pop because of the air pressure. The hot, humid air immediately brushed our skin as we exited the elevator. Though the cave ceiling was high and a big fan was circulating the air, it still took me several minutes to regulate my breath until I could breathe normally.

Our guide, Miriam, showed us around and explained how things work while sharing her experience as a woman working in underground mining. Having studied Geotechnical Engineering, Miriam is an excellent rock mechanic. Her expertise is needed to design efficient and safe methods for excavating and extracting minerals by analyzing how the rocks behave under the earth’s surface. Hence, permission to work underground was acquired.

Miriam (in blue) is showing us how she investigates rocks’ stability underground (Daniel Chrisendo)

“I am often underheard,” Miriam reflected with a fond smile. “Sometimes I have to show two or three times more effort and speak louder, so people take me seriously. They laugh at my ideas.” She giggled, thinking about it.

I was surprised at how advanced the mine operation was. Almost everything was run by robots and machines. Rocks were exploded, broken into pieces, transported, and brought to the surface using mechanized tools. Human operators just had to press buttons and monitor that everything was going smoothly.

“Underground mining is highly mechanized. The image of people carrying around heavy rocks on their back is usually the image of on-the-surface artisanal small-scale mining,” Miriam explained. “Without advanced technology, it is almost impossible to go underground.”

It then struck me. Suppose excessive human power is not needed for most underground activities. In that case, women should be able to work in such an environment. It does not mean that working underground is not dangerous. It is risky and challenging not only for women, but also for other genders. In fact, I had several small panic attacks and almost fainted because of the lack of oxygen. There are, of course, genuine concerns about the danger of the mining environment on pregnant women, and this argument is mentioned several times in the discussion of why women should not work underground. Yet women should not do many things during pregnancy, including riding the roller coaster. But they are never banned from riding roller coasters.

The intention to protect women should not violate women’s rights. It should provide a safe space for women to work and move instead of discriminating and limiting women’s opportunities. Eventually, women may or may not want or appreciate underground and on-farm work. And this is okay. But if they want to, they should be able to do it safely without having to face legal and social barriers.

I, again, would never understand how it feels to be a woman in Sudan, Mexico, Indonesia, or Zambia. But I hope we all can agree that gender equality is a fundamental human right, regardless of where we live.

Daniel Chrisendo is a postdoctoral researcher at Water and Development Research Group, Aalto University. His research interest includes sustainable food systems, gender equality, and people’s wellbeing.