In this blog post WDRG post-doc Laura Verbrugge reflects on the role of researchers in transdisciplinary research projects on water.

Solving wicked problems in water management requires collaboration of various actors and the integration of knowledge from diverse sources and research disciplines. Such processes, also referred to as knowledge co-production, help to establish a common understanding of the problem(s) and a common ground for collective action. For example in Finland, stakeholders have developed a shared vision for several river basins, such as the Iijoki, Kokemäenjoki, and Oulujoki rivers. These visioning processes aim to strengthen the commitment of various parties, take different values into consideration, and ensure that the work will continue in the future.

Scientists can take on different roles in such multi-actor projects, ranging from a fly on the wall to an active change agent. Each role may have certain benefits and trade-offs for knowledge co-production processes and outcomes. But how do you navigate these different roles and what does this mean for your research in practice?

Multi-, inter-, and transdisciplinary research

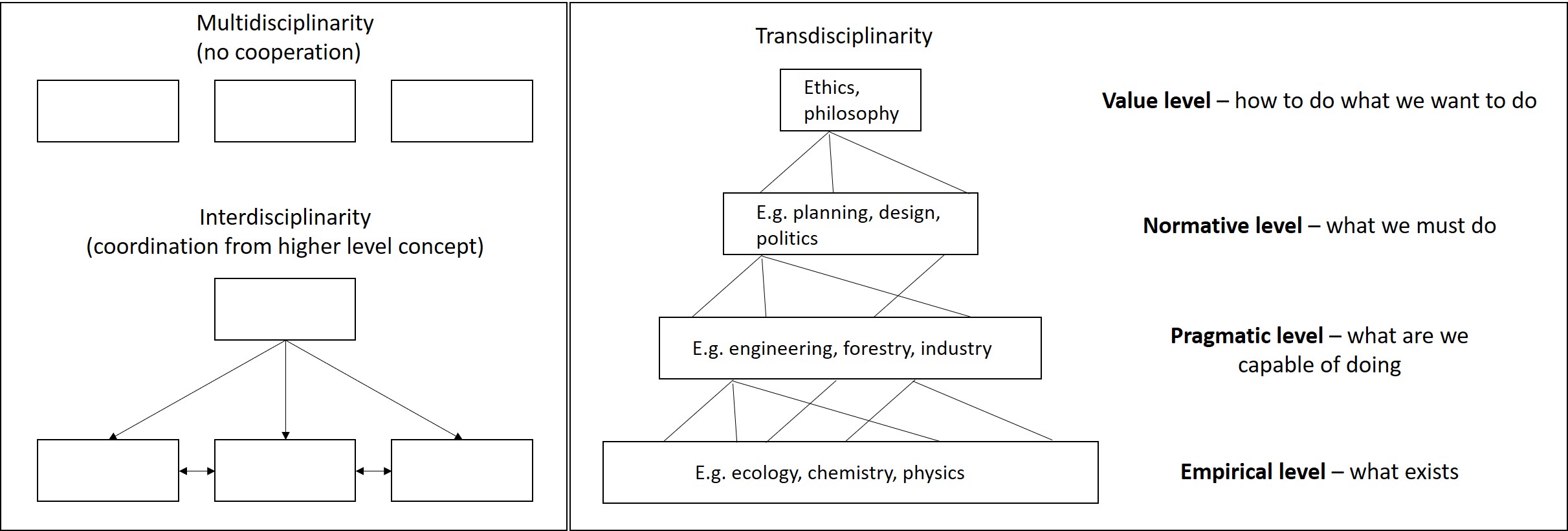

Let’s start by looking at the different types of research that scientist can engage in. Often a distinction is made between multi–, inter– and transdisciplinary research (Figure 1, adapted from Max-Neef 2005). In multidisciplinary research, scientists carry out their analyses separately *using discipline-specific methods and knowledge) resulting in reports without any integrating synthesis. Interdisciplinary research involves scientists from different disciplines to bridge the gaps between empirical, purposeful, normative or values research. For example, agriculture combines empirical knowledge from chemistry, soils, sociology and biology. According to Max–Neef (2005), a transdisciplinary action is defined as any multiple vertical relations that includes all four levels of research (Figure 1).

Multiple definitions of transdisciplinarity exist, with most recent ones emphasising the inclusion of knowledge provided by non-academic actors. A recent OECD report (2020), summarizing 50 years of transdisciplinarity research, defines it as “research that integrates both academic researchers from unrelated disciplines […] and non-academic participants to achieve a common goal involving the creation of new knowledge”. The same OECD report highlights two challenges for conducting transdisciplinary research. The first is how to select and effectively engage non-academic stakeholders, and the second concerns the ethical considerations that often arise from this engagement. Here, I would like to add another challenge: are researchers equipped with the skills and expertise to guide the creation and integration of new knowledge?

PlanSmart + RiverCare = SmartRiver Symposium

How can we, as researchers, examine, promote or facilitate the co-production of knowledge, and what are the implications, trade-offs and benefits of taking on a specific role?

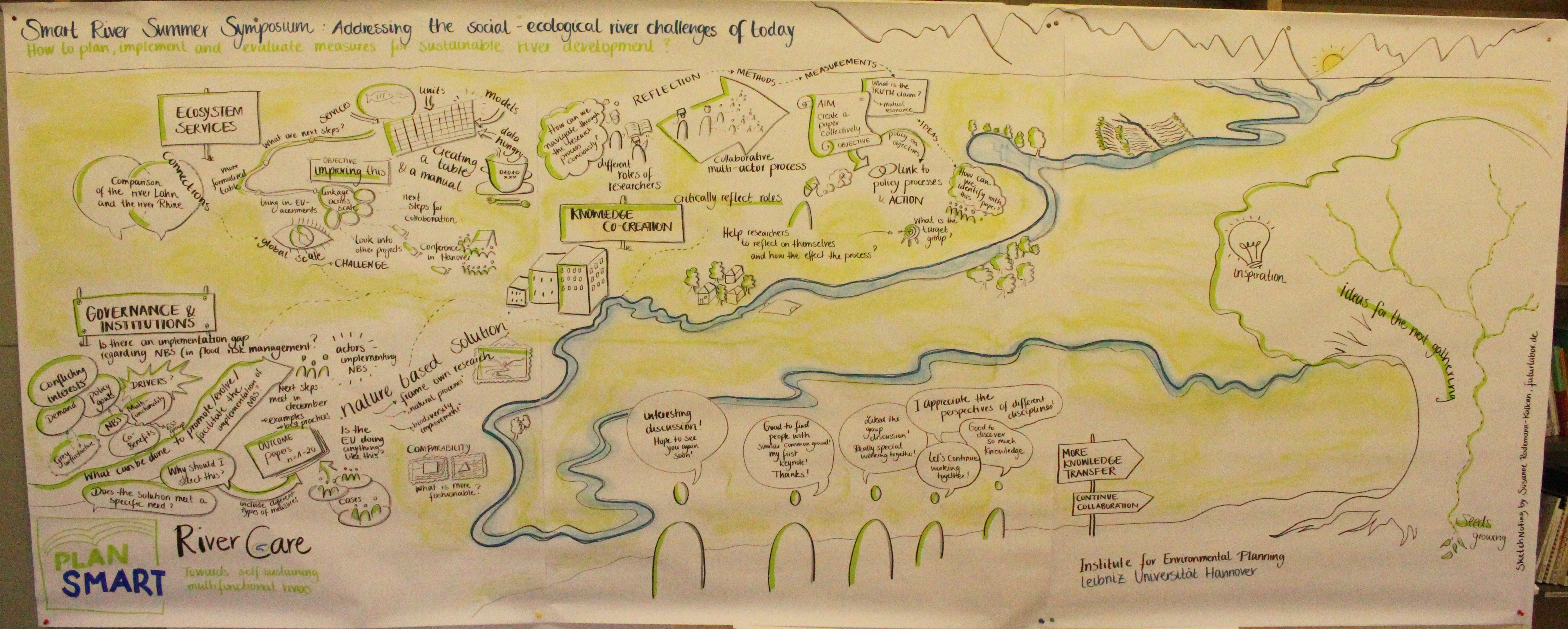

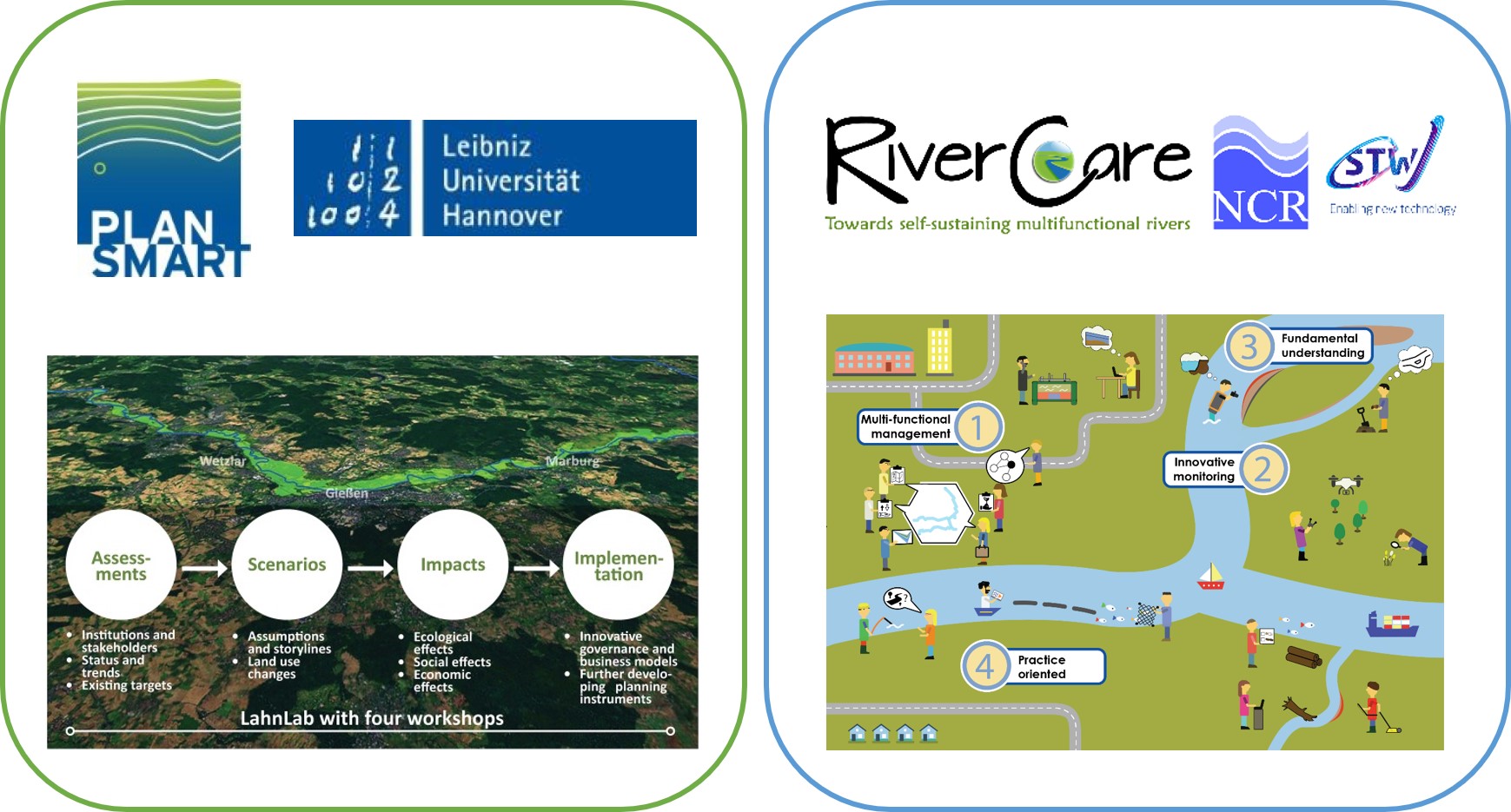

This question was the topic of discussion during a joint symposium of two transdisciplinary river research projects held in 2018 (Figure 2). PlanSmart (2016-2021) is an interdisciplinary research group that works together with societal and governmental actors to co-develop and support the implementation of nature-based solutions in the Lahn River in Germany. RiverCare (2014-2019) was a Dutch research program in which five universities collaborated with stakeholders to monitor the effects of large-scale river interventions and implement sustainable management practices. In both projects knowledge co-production processes were facilitated through a variety of methods, including workshops, user committees where stakeholders are actively involved in guiding the research, and participatory methods.

Knowledge, stakeholder and research spaces

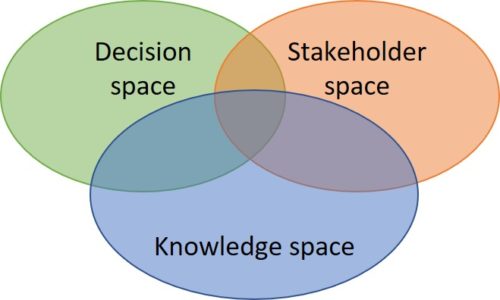

The SmartRiver symposium marked the beginning of a joint reflection on researcher roles in the increasingly diversifying and politicized playing field in water research. One important outcome was the recognition that, as a researcher, you are working at the interface of multiple ‘spaces’ (Figure 4, adapted from: Vinke de Kruijf et al., submitted). The one most familiar to a researcher is the knowledge space where scientific knowledge is produced and integrated from different disciplines. Interaction with actors outside academia (such as citizens, government organizations, or transboundary river committees) takes researchers to the societal realm (or stakeholder space). Researchers are also increasingly confronted with norms and values that favour or dismiss certain solutions to water problems, making them aware of the decision space where political choices are made.

How to navigate transdisciplinary waters during your PhD?

While this may all be somewhat overwhelming for a (starting) PhD candidate, or any researcher involved in transdisciplinary research projects, there is no need to despair. Education is rapidly evolving to train the next generation of scientists, with the ongoing Majakka doctoral supervision project at the Water & Development Research Group as an excellent example.

On a personal level, reflection is key. Here just remember to hang on to the ROPE guidelines developed during the SmartRiver symposium (Vinke de Kruijf et al., submitted):

Resources – do you have the capacities and skills to fulfil your role(s) and is there enough time and financial support available?

Orientation – are you aware of your normative orientation with regards to the content and impacts of your research?

Position – are you aware of how your research is positioned in relation to the three spaces?

Expectations – have you clearly communicated the goals and potential impacts of your research?

When you take enough time at different stages of your project to reflect upon these four elements, you are better prepared for the tasks ahead of you!

Laura Verbrugge is a postdoctoral researcher at the Water and Development Research Group. Laura has a PhD in Environmental Science and her work aims to connect people and knowledge from different disciplines to solve problems in environmental management. She combines her research activities with providing doctoral supervision support in the Majakka project.