The effects of climate change can be seen in many different aspects of our lives. One of the most concerning effects is the far-reaching impact it has on agriculture. When climate change causes extreme weather conditions, it can damage crops, leading to lower yields and higher food costs. To combat impacts of climate change, farmers are taking a variety of agriculture practices, such as using cover crops, reducing tillage, and irrigation. In recent years, crop migration has also been taken into account in food security analysis.

Crop migration refers to the movement of crops to different geographical areas due to changes in environmental conditions, mostly temperature and precipitation patterns. As temperatures rise and weather patterns become more extreme and unpredictable, traditional crop growing areas may no longer allow for efficient crop growth, forcing farmers to alter crop varieties to more suitable ones or even relocate crops to new areas with more favorable conditions. This can result in changes in the distribution of breadbaskets and the availability of food, as well as economic and social consequences for the affected communities.

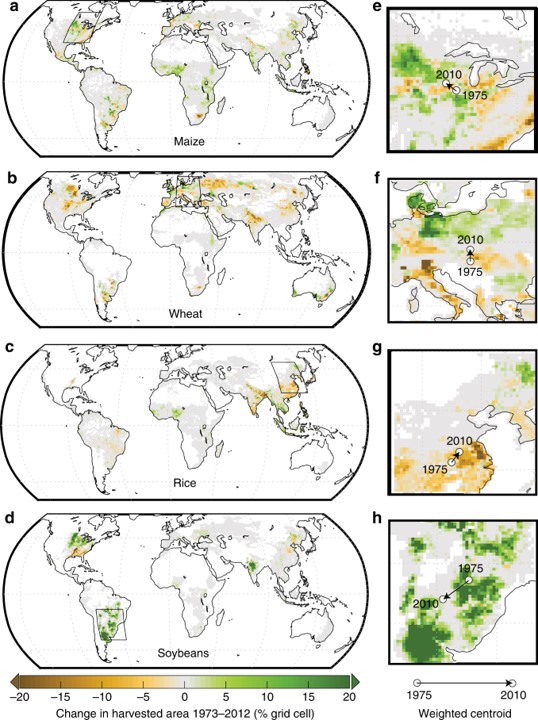

Previous studies have demonstrated that how changes in rainfed crop areas and crop migration in turn moderate the negative effects of climate change in last 40 years. Sloat et al. (2020) showed that crops have shifted away from warmer areas towards cooler areas (See Figure 1). Notable regional patterns of rainfed harvested-area change include a northwestern shift of maize in the U.S., a northerly shift of wheat in eastern Europe, a northward shift in rice in China, and a general increase in soybean in Brazil and Argentina.

Figure 1 Trends in rainfed harvested area between 1973–2012 (Sloat et al., 2020)

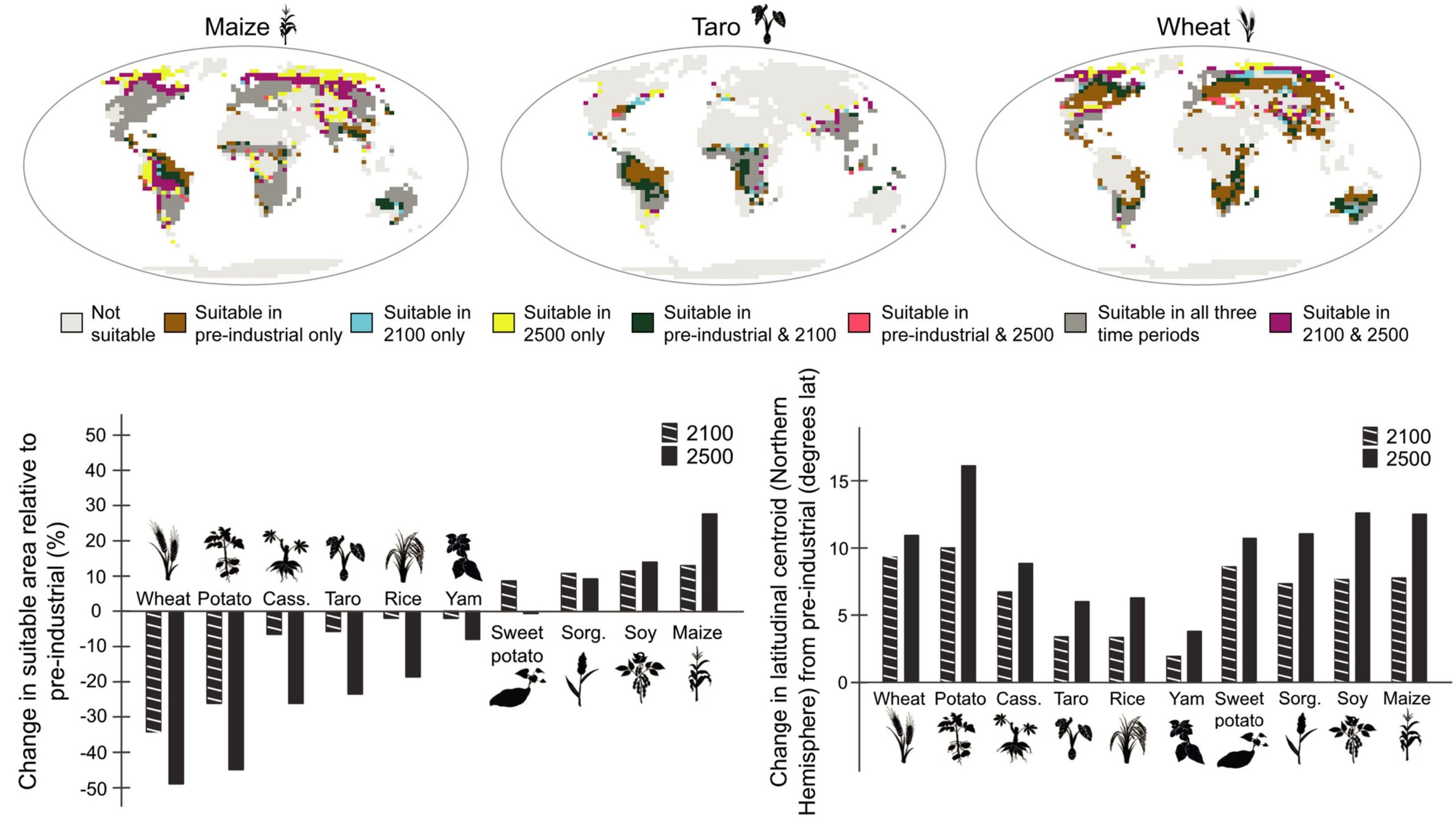

Climate-driven crop migration has been projected for the future as well (Figure 2). Suitable regions are projected to shift poleward for both hemispheres, although greater shifts are projected in the Northern Hemisphere. By 2100 under RCP6.0, the land area suitable for both major tropical and temperate crop growth would be declined, and there would be a double decrease of suitable crop areas by 2500. Besides, in terms of specific crops, wheat, potato and cassava are projected to lose the largest growing areas of crops by 2500 while soybean and sorghum would maintain a stable growing area even after crop migration. It’s mainly due to wheat, potato and cassava are mostly located in more vulnerable areas like Africa and the Middle East, and sorghum is more tolerant to heat and drought than other crops.

Figure 2 Projections for crop suitability to 2100 and 2500 under RCP6.0 (Lyon et al., 2021)

Overall, crop migration substantially moderates the impacts of global warming, but continued crop migration may lead to the loss of biodiversity and increase the spread of pests and diseases due to habitat loss and changes in phenology. Nevertheless, crop migration is becoming more and more common. Thus, it is essential that we take action to develop sustainable crop adaptation solutions, as the effects of climate change will only get worse in the future.

Reference

Sloat, L.L., Davis, S.J., Gerber, J.S. et al. Climate adaptation by crop migration. Nat Commun 11, 1243 (2020).

Lyon C., Saupe E.E., Smith C.J. et al. Climate change research and action must look beyond 2100. Glob Chang Biol 28, 349 (2022).

Qiankun Niu is a doctoral researcher at Water and Development Research Group, Aalto University. Her research interests include climate change adaptation, and land-food-climate nexus.