This blog post reflects my recently published peer-reviewed article, co-authored by Professor Keskinen (Haapala & Keskinen, 2022). The article reviews the history of Finland’s cross-boundary cooperation with Russia, focusing on the development of water diplomacy and water cooperation. In particular, the article presents how the development trajectories of transboundary water interactions are related to more general socio-economic trends and historical occurrences. The study shows how transboundary water interactions have evolved from a deep post-war state of mistrust towards routine cooperation.

Transboundary waters typically need to be managed through a joint mechanism. These practical mechanisms include water diplomacy and transboundary cooperation institutions. In short, transnational water diplomacy is important in the political negotiation of agreements and rules for the management of shared waters. As a result of diplomacy, transboundary cooperation institutions are established to implement these agreements and rules on the basis of their mandate. The Finnish-Russian Transboundary Water Commission is a good example of such a body for transboundary cooperation. The article uses these two concepts as the theoretical departure point and elaborates the ways in which these concepts relate and interact in practice over a long period of time.

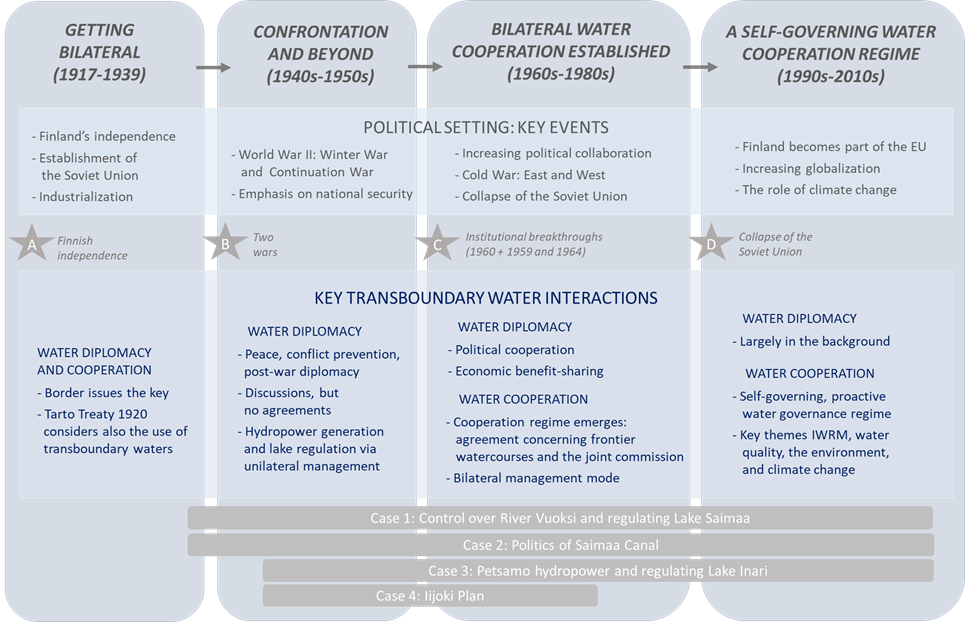

The findings are divided into four periods: 1917 to 1939, 1940s and 1950s, 1960s to 1980s, and 1990s to 2010s, presented in a nutshell below:

While detailed elaboration of the findings is not possible in a blog context, the main features of the development of Finnish transboundary cooperation can be highlighted in a nutshell. I emphasize that water diplomacy and transboundary cooperation are driven by domestic political pressures, in which national identity and state-building play a major role. On the other hand, it is also driven by external pressures, such as securing national sovereignty in Finland’s geopolitical environment, military and legislative pressures, and megatrends such as climate change and digitalisation. Third, the development of transboundary water interactions is influenced by the advantages and disadvantages of the location not only on the upstream and downstream axes, but also in terms of geopolitical tensions due to the proximity of strategic sites such as rapids, mines, and industrial cities.

The study shows that the management of shared waters transcends individual river basins and extends across a number of policy areas, from energy policy to national security. On the other hand, political forces and power games alone are not the drivers of change but are the long and extensive costs of socio-ecological and technical-scientific development. The case of Finland-Russia shows that even a weak starting point can result in a functioning, developing and mutually beneficial water cooperation. Water diplomacy was needed to create formal institutions for transboundary water cooperation that, since their inception, have operated relatively independently of the historical twists and turning points, effectively adapting to world’s change.

This summary post was written by PhD Juho Haapala.

Reference

Haapala, Juho, and Marko Keskinen. 2022. Exploring 100 Years of Finnish Transboundary Water Interactions With Russia: An Historical Analysis of Diplomacy and Cooperation. Water Alternatives, 15:1.